New Ways of Seeing

“Le Village” by Luc Delahaye and “AO” by Charlotte Dumas make us modestly rethink our perspective on the world

Huis Marseille, Amsterdam, 11 December 2021 — 08 May 2022

*This essay was written for the course “Design in Words” in Spring 2022 during my Master’s “Comparative Arts and Media Studies”

In his new body of work “Le Village”, French photographer Luc Delahaye depicts life in a small Senegalese village. With the focus on everyday heroes, village scenes and local mythologies, he combines large-scale photographic tableaux with documentary series. At the same time, Dutch visual artist and photographer Charlotte Dumas has studied the Japanese island of Yonaguni and its critically endangered breed of native horses that roam it freely for “Ao”. Both exhibitions were displayed at Huis Marseille and put both non-human and human interaction at the centre.

“Put yourself first” is a mantra that we often find on social media, along with #selfcaresunday or #metime. Don’t get me wrong, caring for your mind and body is essential for a healthy and happy life (here we go with more postcards slogans), but putting yourself first as a human and therefore above else, has its critics. Justifiably so. Humans have been exploiting nature for many years now. By overconsumption, population growth and intensive agriculture, we humans are pushing the planet’s life-support systems to the edge. While we live in the era of the Anthropocene, have we even noticed how, while we are all putting ourselves first, heavily we have impacted the Earth’s geology, ecosystems, and overall, the climate? Clearly, if you haven’t been living behind the moon, this is not news. Good morning, #Fridaysforfuture!

However, while young people around the globe protest for a greener future and while politicians around the globe discuss new climate goals, the (capitalist) system remains sluggish. Some scholars go as far as tapering the Anthropocene to a Capitalocene. Hence, while brands reshape their marketing strategies, while the media preaches sustainability, while the population grows and while Silicon Valley works on parallel worlds such as the Metaverse to make people even more dependent on and addicted to their digital devices, our (capitalist) society remains sluggish. But I’m getting cynical.

“Consumerism is best understood as a cultural condition in which economic consumption becomes a way of life.”

- Steven Miles, Consumerism as a way of life London: Sage, 1998

Sometimes you get the impression that you can scream and scratch and stomp, but no matter what you try, you don't change anything. So why even start? And even though art and culture have been called not-system-relevant during the last two years and thus under the pressure of the Corona pandemic, I argue vehemently against it. Because art and design hold up a mirror to us and our society, our attitudes, and our approach to life. This, just like self-reflection, may not always be comfortable, but it is necessary - more than system relevant, I would say, absolutely essential.

That is exactly why I now recommend the two photography exhibitions at Huis Marseille. Since Delahaye and Dumas decelerate our capitalist focus and let us see that ‘around us’ in a new way. Their eye captures their subjects gently and calmy and lets us remove the blinders we might have been wearing. I stand in front of Delahaye’s “Le Champ” (The Field), almost smelling the air and feeling the dirt. I sit in front of Dumas’ “Yorishiro”, almost feeling the wind and tasting the salt. The rooms at Huis Marseille are scarcely decorated, allowing the photographs and video screens on the walls to unfurl, allowing me to wander into different realities and to sense different worlds. But enough of the prefaces, let’s dive in further, shall we?

Luc Delahaye and “Le Village”

The photographer Luc Delahaye (born 1962, France) has become known for his large-scale colour works, focusing on conflicts, world events and social issues. While he began his career as a photojournalist in the mid-1980s with reports from war zones for the French news agency Sipa Pres and joined Magnum Photos in 1994, he left the latter ten years later. Now, his works, at times, are reminiscent of history paintings or Christian imagery of the victim. They can be further characterized by detachment, directness, and rich detail. His documentary approach counters dramatic intensity and a narrative structure. Huis Marseille summarizes: “Within their visual coherence these images express a nub of formal tensions, aesthetic and political stakes. They are documents-monuments of immediate history, and they urge reflection upon the relationship between art, history and information.”

“Le Village” portrays people in a remote place, while it also illustrates the local mythologies that are transmitted through generations. Delahaye pays tribute to the everyday, while referencing the spiritual world of djinns, to local legends and, much like his former works, to religion. For “Le Village” Delahaye lived for a period of several months in a village in the Futa-Toro region of northern Senegal, near the river for which the country is named after. He had come across this place some years before and had stayed in touch with one of its inhabitants. In 2019, they agreed on letting Delahaye stay there. “This place is an ordinary, unremarkable Senegalese village. It’s a small community in a limited space. I wanted to be in such a place and stay there a large amount of time in order to approach its smallest aspects and give them the meaning they deserve.” A man mending his fishing net, the ritual sacrifice of a ram, a quiet interior scene, or a man working alone in a field – these are the themes Delahaye catches in “Le Village” to describe a prosaic reality without details or symbols, but the sheer presence of the people and themes represented.

Capture Sacrifice d’un belier, Luc Delahaye, 2019. Photography by author, March 13, 2022.

In “Sacrifice d’un belier” (Sacrifice of a Ram) we bear witness to the slaughter of a ram that itself is the protagonist of the photograph. Delahaye himself describes this picture as an “opportunity to make a convincing portrait of an animal.” Although it depicts the drama of death, it emphasizes the sanctity of the ritual and the Senegalese people’s worship of the animal as representative of the non-human.

Charlotte Dumas and “Ao”

Dutch artist Charlotte Dumas (Vlaardingen, 1977) focuses on animals in her photographic portraits, as much as she does on humans, “insofar [...] we reflect ourselves in animals.” Focussing on composition, light, and the poses of classical portraiture, she draws from what she calls “traditional ingredients” of 17th-century Dutch paintings. She works in series, based on themes drawn from life and literature, and has captured police and military horses, wolves in the wild, tigers in captivity, and stray and working dogs. Dumas humanizes them by shooting at a range that allows intimacy without invasiveness. She states: “My choice of subject relates directly to the way we use, co-exist with, and define specific animals, assigning various symbolisms to them as well as our own personal reflections.”

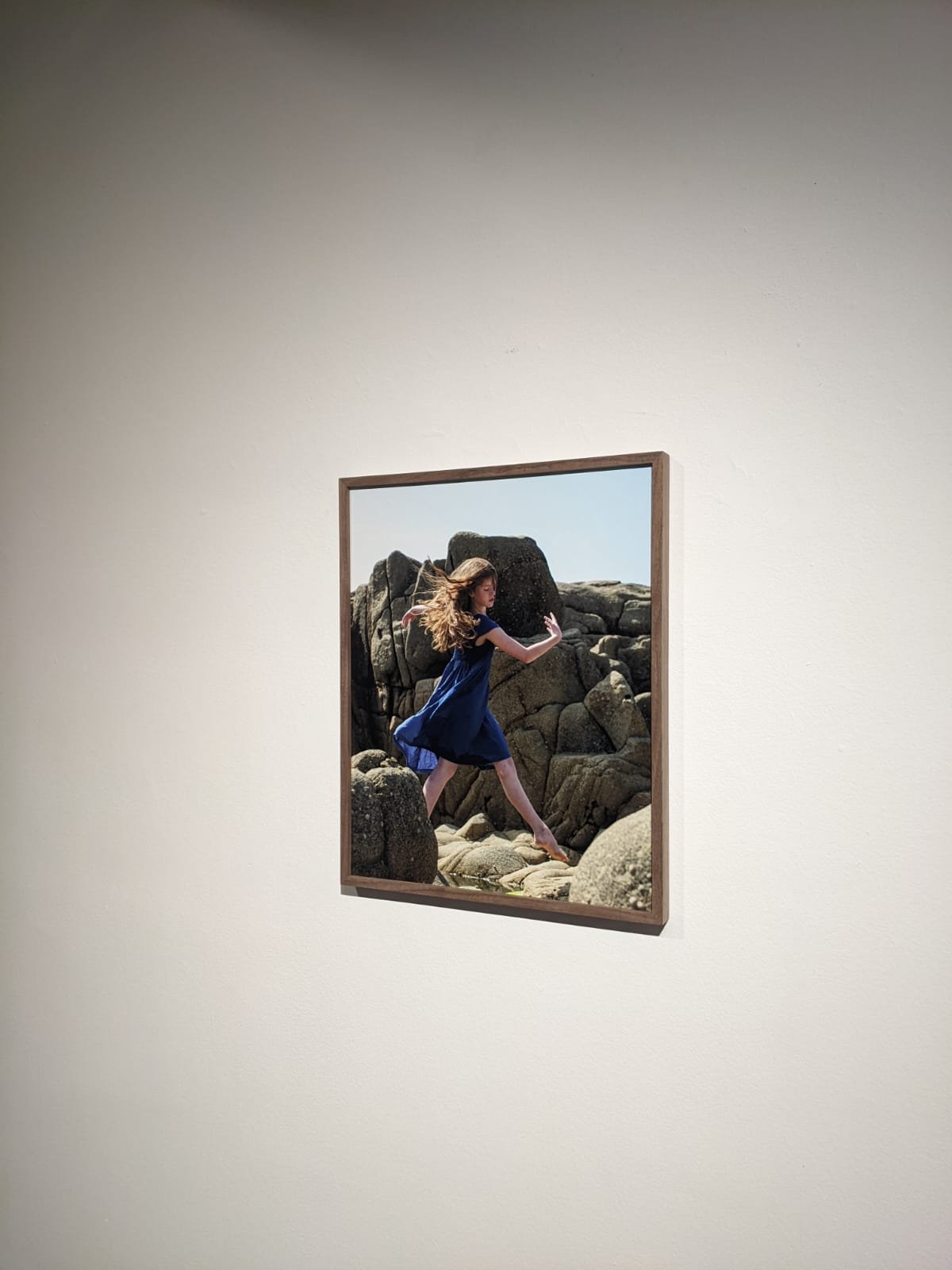

Piece of Charlotte Dumas “Ao”. Photography by author, March 13, 2022.

Piece of Charlotte Dumas “Ao”. Photography by author, March 13, 2022.

One the one hand, she describes a contradictory relationship between animals used and seen as a food resource and the anthropomorphic use of them on the other, as often depicted in visual language. The artist says that she is particularly interested in the complexity of how we define value to our selves and others.

“It is my belief that the disappearance of the actual presence of animals as a given in our society greatly affects how we experience life and influences our ability to be empathetic with one another.” - Charlotte Dumas

In “Ao” 青 (‘Blue’), Huis Marseille shows three overlapping films, complemented with photos from the same project. Dumas has studied this island and the endangered breed of native horses there since 2015. Through her intimate films and photos, the visitor is also introduced to a tragic part of the island. Due to the industrialization and the import of larger Western breeds, the island’s little horses lost their practical usefulness what led to a drastic decline in their numbers. However, these horses were not only used as general workhorses but also fulfilled a religious function. Yonaguni horses now can still be seen on the island and have been declared a protected living heritage. Besides the horses, girls also play a role in Dumas’ films. In their innocence, the girls symbolize a touchpoint of humans and nature that is in turn embodied by the horses.

Get (back) in touch with...

Albeit very modest, both exhibitions let the visitors subtly reflect on their role within society as well as the aggregate of our society in general. What is the relationship between non-human and human? How are the ways of life, agricultural techniques and spiritual beliefs of former generations replaced or even extinguished by today’s aestheticization and stylization of life through industry and with technology?

Capture Évocation de Penda Sarr, Luc Delahaye, 2019. Photography by author, March 13, 2022.

Today, we only see the finished product and thus do not come into contact with the tree on which the apple grew or the field from which the cotton for our T-shirt was produced. Today, we no longer live with animals, except when we keep them as our pets. We don't watch them navigate their surroundings, see them take from but also give back to nature. At Huis Marseille, attentive and sensitive visitors come to reflect and rethink their material world and their place within it. The mostly photographic works make us rediscover relationality and interconnectedness with ‘the around us’, while they are the paradox we might need. The exhibition itself remains surficial due to its clean display. As we stare at the artworks, our own faces mirror in the glossy prints of the exhibited photographs, yet the artists manage to catch us and get us out of our hectic strive of consuming, with directing our gaze towards, and therefore embracing, the calm continuity of animals and nature.